Did Evolution Make Us Into Psychological Egoists?

I will be making the case that there is no reason to suppose that evolution has made us into psychological egoists. Sober and Wilson1 put forward four compelling arguments to motivate psychological altruism; pluralistic structure of altruism, generation of sufficient emotions, belief emotion dependency and maladaptive updating. Each of these is independent of the other and a lot can be said about the merits and possible responses to each of them. I will focus on the last one. This argument is supposed to show psychological egoism is not our default position. Stephen Stich2 has invoked recent findings in cognitive science in particular subdoxastic ‘sticky’ states as an objection to this account. I will assess this objection and

show that it is unsuccessful.

Psychological Egoism and Altruism

Altruism can be defined in a number of ways however in a biological context it has a particular meaning, a behaviour is evolutionarily altruistic if its consequences lead to the

enhancement of another organism while incurring a cost to itself. Evolutionary altruism is not concerned with what the psychological motive behind the act is or even if the organism has a theory of mind, all that matters is the action itself. Psychological Altruism is a motivational

state, where a subject intends to help another not for a reciprocal gain or any other benefit but for the other’s sake as the ultimate end. Conversely Psychological egoism is a motivational

state in which one’s ultimate desire is for one’s own selfish interests.

One can do acts that benefit others in the sense of evolutionary altruism and yet be a psychological egoist. Suppose you see someone helping a friend to move home, they spend hours loading and unloading without payment, now you may question them why they are doing this and they answer honestly that they want to help. It is tempting to say that they are a psychological altruist, as not only does their action benefit others, they actually want to help, however this is not enough. It might be the case that they helped as this gives them a sense of self delight and saves them the cost of working out at the gym. It could be the welfare of the recipient is not an end of itself for the helper, rather it is just a means for a deeper selfish goal, in this case their desire can be said to be merely instrumental rather than ultimate. To

see if a person is motivated by a purely altruistic state we need to see not just if they want to help but Why they want to.

Proponents of psychological egoism would be committed to the idea that psychological

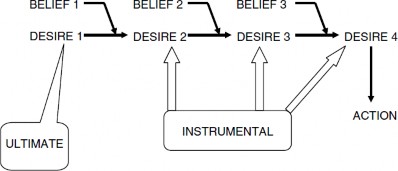

altruism is a useful fiction, and that our motivational state is always lead by selfish goals, any altruistic behaviour is reducible to egoism. Our desire to help others is an instrumental desire, it is always a means, never an end of itself. Conversely proponents of psychological altruism claim that we can sometimes behave in way that benefits others in an irreducible way, we are capable of sometimes helping others as an ultimate desire in of itself. Instrumental desires are derived from ultimate ones by means of intervening beliefs or belief-like states.

|

Figure 1.3 Instrumental desires are formed via a causal reasoning process that involves a desire and a belief. An ultimate desire is not produced by this process but rather it is the starting point for it.

It is also helpful to tease out self-directed and other-directed preferences. The former is describes the state of the agent exclusively such as an agent wanting himself to succeed, the latter is the state an agent holds for another not himself such as an agent wanting another individual to succeed for that individuals sake. Instrumental desires

hide self-directed preferences as other-directed ones.

Now suppose that an agent only chooses a behaviour based upon what maximises the

satisfaction of their preferences, say a final year student chooses to donate all her books to a fresh undergraduate. She can perform this action with a number of preferences, she may want to help someone as that is what she thinks will bring her status up in eyes of her recipient, or perhaps she wants to give her books away so that the recipient is better off. One of these

preferences is self directed and other is other directed. Using these two preferences Sober makes the following four labels.

Extreme Altruism – Agent cares only about others Extreme Egoism – Agent cares only about themselves

Moderate Egoism – Agent cares about themselves and others Moderate Altruism – Agent cares about themselves and others

When the preferences of others and the agents converge then both Extreme Altruists and Extreme Egoists perform the same action. Both these categories describe people that have one kind of preference. Where an agent has a mixed preference like a student who wants a better status and wants to help another student, again the same action will be performed if the preferences converge, but the difference is when the preferences are in conflict. This is where the moderate egoist will chose self interest over welfare of others and the moderate altruist

will chose the other over herself. So in the case of the final year student, she may want to be acknowledged by the recipient student and help them but if she is a moderate altruist, the discovery that the recipient is an ingrate who doesn’t recognize a favour will not affect her decision to give the books away, however a moderate egoist on the discovery that the recipient is an ingrate and another undergraduate student is not will be affected by this

conflict of preferences and will not give the books away. What really matters is what an agent does when the self directed and other directed preferences are in conflict, this is how to distinguish between psychological altruism and egoism, the former will chose others over themselves and the latter wouldn’t. A moderate egoist has Instrumental desires to help and these make them help until there is a conflict between their ultimate self directed desires and

these other directed instrumental ones. Of Course this is not to say a person will be an altruist only if they choose other directed preferences every time a conflict between preferences

arises, they may shift from situation to situation.

Reliability of Psychological Egoism

If an action is fitness advancing natural selection can build within the organism a mechanism that is triggered in the appropriate circumstance. For a general long term behavior like parental care for children natural selection may build a proximate mechanism that is triggered to get organisms to care for their children. Here we can make a distinction between the ultimate explanation, natural selection gearing parents to increase reproductive fitness and the proximate mechanism, care towards children.

To get us to act in altruistic or selfish way natural selection needs an appropriate proximate psychological mechanism. It would be tempting to say that evolutionary selfish behaviour is triggered by a selfish mind and evolutionary altruistic behaviour by a altruistic mind, however this needs some justification, as it is possible that both types of psychological states can explain evolutionary altruistic and selfish behaviour. For example suppose parent A takes care of their children as she has an ultimate desire that is other directed, and parent B also takes care of her children but her ultimate desire is self directed and she has a belief that her happiness is linked to that of her children, so she has an instrumental desire for parental care, both parents take the same action based on different proximate mechanisms. Sober argues there is no a priori reason to think that natural selection would favour a selfish psychological mechanism for selfish behaviour and an altruistic psychological mechanism for altruistic

behaviour4. In the case of parental care we need to decide between two hypothetical proximate mechanisms:

(A) Parents care about their children not as a means of their own happiness but as an end in of itself.

(E) Parents care about their own welfare and they are disposed to link their own welfare with that of their children.

Parental care is a good case to test as it is not only evolutionarily altruistic, it also increases the inclusive fitness of the parents and as such there would have been significant selective pressures to build proximate mechanisms that ensure such care is given.

Psychological altruism (A) is a direct solution to the getting organisms to care for their children, for the easiest way for natural selection to ensure care is provided is to endow

parents who do actually care about their kids as an end in of itself, conversely psychological egoism (E) would be an indirect solution. It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that

altruistic behaviour is due to an altruistic mind simply because it is a direct solution. We know of cases where natural selection has lead to indirect solutions where at first it would seem obvious that the easiest solution would have been the direct one. Sober points to the

fruit fly as an example, it is evolutionary advantageous for them to find places that are humid, a direct solution would have been to give them inbuilt humidly detectors. Fruit flies have no

such thing instead they have the ability to detect where dark places are and there is a

correlation between these dark low light locations and humidly, natural selection has chosen an indirect solution as it has to juggle between competing variables. Sober and Wilson argue

for three component criteria for natural selection to decide which solution to opt for, reliability, availability and energetic efficiency.

In terms of availability it can be argued that the mental framework needed to for (E) to be a proximate mechanism would be sufficient to allow (A) as well because implementation of (E) would include beliefs. Recall that (E) means that parents not only care about their welfare but they believe their welfare is linked to that of their children. For an egoist parent to maximise his or her preferences they must have the ability to detect if their children are doing well.

After detection they have to form beliefs with content such as ‘my child is ill’ and ‘my child is healthy’. Since they can form beliefs about a state of affairs p, they can also form desires about if p should or should not be the case or if another state q is desirable.

It is true that the altruistic desires as an end what an egoistic desires as a means but this distinction Sober thinks does not affect the formation of the basic belief/desire structure, if someone claims (E) is available but not (A) they need to put forward a argument, by default

(A) and (E) should both be accessible proximate mechanisms, I think this is a safe assumption and it makes (A) and (E) on equal footing.

Energy efficiency would certainly have played a substantial role on the selection of (A) or

(E). And there is a lot that can be said about the energy efficiency of some biological features that have been extensively studied. However we don’t have enough plausible hypothesis on the evolution of the human mind to make justifiable claims on how one state may be favoured over another. So it is best to assume both states are on par in terms of this variable.

Thirdly reliability is where Sober and Wilson think there is a major difference between (A) and (E); the possibility of maladaptive updating makes (E) less reliable. Recall for the psychologist egoist care towards their children is based on a correlation between their

children’s happiness and their own happiness, if children are in pain then the egoist parent feels pain so she must help, but what if her belief that ‘my children are in pain, so I am in pain, I must help them’ is updated to ‘my children are in pain, so I am in pain, I must take Heroin to feel better’. Nothing can stop this untoward updating as it’s just a replacement of an instrumental desire by another one to achieve the same outcome. There lots of ways of gaining happiness and relieving pain can be done that are simpler and more accessible than childcare, parents with such mindsets would hardly be ideal for natural selection. Sober & Wilson conclude ‘…[The] instrumental desire will remain in place only if the organism… is

trapped by an unalterable illusion.5 Conversely parents who are psychological altruists would not be prone to such maladaptive updating as their motivation to help is based on an ultimate desire that is other oriented, ‘I must help my children for their own sake’. Therefore (A) is more reliable than (E) and is fitter and more likely to be true.

Although Sober & Wilson do not put their argument into a single clear master argument, I think this is an accurate representation of their view:

SW1 Evolution can use a proximate mechanism to solve a problem directly or indirectly SW2 Psychological egoism and psychological altruism are proximate mechanisms

SW3 Proximate mechanisms are selected based on availability, reliability and energetic efficiency

SW4 If psychological egoism is available as a proximate mechanism then so is psychological altruism

SW5 Psychological egoism and psychological altruism are on par in terms of energetic efficiency

SW6 Psychological egoism is less reliable as it is prone to maladaptive updating Therefore

SW7 There is insufficient evidence to think evolution has lead to psychological egoism as the default position

SW7 seems like a modest conclusion if the above premises are true, yet this is as far as Sober and Wilson want to take it, they aren’t aiming to show psychological egoism is false or even that psychological altruism is our state, rather they have a humbler aim of dislodging the burden of proof in favour of psychological egoism and want to motivate psychological

altruism off the ground as it were. Proponents of psychological egoism would focus their attack on SW6 and here is where Stich also directs his efforts.

Stich’s sticky states

Stephen Stich acknowledges that learning can easily change instrumental desires. He accepts the Sober and Wilson’s argument in principle is valid however he thinks they haven’t

considered recent findings in cognitive science which made SW6 untrue. Stich points to subdoxastic states also known as sticky states, these are mental states that are similar to beliefs in the ways they operate, they represent what the world is like, however they are

particularly different to a subjects normal beliefs because they are not updated or changed

easily. They are not introspectable and stick around the cognitive system even if they are falsified. So it can be argued that the sticky mental states ground the desire for parental care or any other type of helping behaviour, therefore these are not prone to updating after all. The upshot is that sticky states work just as a stopper for maladaptive updating.

Armin Schulz6 notes the seriousness of this Stich’s objection, he thinks there are three possible responses to it. Firstly we can question the very existence of these sticky states and there is some criticism out there we can latch on to, however he thinks this is a long shot as they are too widely accepted for a full frontal attack on them to work. Secondly we can claim that since these sticky mental states can’t be updated they also give rise to ultimate desires not instrumental ones. If this was true then it would be a serious problem for the egoist as his ultimate desire will have no instrumental veneer so it won’t be involved in the facade of helping behaviour of any kind. This is tempting but Schulz thinks this won’t work either as he notes that these desires only exist because of an agent’s belief like state which happens to be sticky one, so these desires can be instrumental because if the organism would not have these desires then the corresponding belief like states they are grounded upon would be in one way or another dislodged from an agent’s cognitive system. Schulz agrees with Stich that this would be the case even if a more nuanced definition of instrumentality is used. Schulz

argues that the only viable response is simply to accept Stich’s objection and concede that

maladaptive updating does not make (E) less reliable and hence Sober and Wilson’s argument does not dislodge egoism as the default position. Schulz thinks this is still good news as even if we accept Stich’s objection, it is not devastating since it just pushes the debate on egoism

considerably forward. Before the discovery of sticky states the argument would have worked, now it rests on testing of the contents of sticky states. Since testing sticky states can be done

now7 the debate about psychological altruism and egoism has moved considerably forward. I think Schulz has given too much ground to Stich. Although he is right about the problems of denying sticky states altogether and claiming that all sticky states are ultimate desires he is hasty in his acceptance of Stich’s objection.

Stich’s argument seems to me to be the following:

S1 Instrumental desires are grounded on sticky states

S2 Sticky states cannot be prone to maladaptive updating Therefore

S3 Instrumental desires are not prone to maladaptive updating

This argument is problematic, is he saying that all instrumental desires are grounded in sticky states, if yes then why is that the case? he needs to give us a compelling argument which he has not done. It is possible that some instrumental states may be grounded on sticky ones but why all of them. Stich may of course respond that not all instrumental desires are sticky

states. In that case his argument is probabilistic as some instrumental desires may be grounded in sticky states while others are not. This would mean that Stich would have to face the problem that a percentage of instrumental desires are prone to maladaptive updates. Since Psychological Egoism is depend on instrumental beliefs for helpful behaviour and this behaviour is supposed to increase the fitness of the organism, then the fact that a percentage of instrumental beliefs are prone to maladaptive updating makes them less reliable and less likely to be fixed by natural selection. Stitch may want to argue that instrumental states that

are free from sticky state influence are low in number. I don’t think he can show this is the

case and even if he could it wouldn’t help him much since natural selection is a highly sensitive force. Parental care is a fitness enhancing behaviour and there must have been

substantial pressures on the selection of the proximate psychological mechanisms needed to ensure such care. As such if even a very small number of instrumental desires are not based on sticky states then they would be prone to maladaptation and hence they will be less reliable.

Additionally consider false instrumental desires which are based on beliefs such as ‘I want to help my children as it will make me taller’, on the discovery that helping their children is not making them taller such a instrumental desire will need to be corrected but on Stich’s account it can’t be altered. So if this is true then we should have all sorts of useless instrumental beliefs which are clogging up our cognitive system, no such evidence exists. On the other hand if Stich wants to argue that only the true instrumental desires are grounded in sticky mental states then he would need to put forth an argument for why that would be case, there does not seem to be any reason to distinguish between true and false types of instrumental desires.

Conclusion

I have made the case that Sober & Wilson’s argument against psychological egoism is persuasive. Maladaptive updating is a serious challenge for egoists and Stich’s response is not compelling. I believe the argument against psychological egoism has managed to successfully dislodge egoism as the default position and it certainly has increased the likelihood of

altruism being our motivational state.

References

- Sober E. and Wilson D.S. 1998. Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Stich S (2007) Evolution, altruism and cognitive architecture: a critique of Sober and Wilson’s Argument for psychological altruism. Biol Philos 22:267–281

- Ibid.

- Sober, E. (1993a). Evolutionary Altruism, Psychological Egoism, and Morality: Disentangling the Phenotypes. In M. Nitecki (ed.), Evolutionary Ethics, SUNY Press, pp. 199-216

- Sober E. and Wilson D.S. 1998. Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.p.315

- Sober & Wilson’s evolutionary arguments for psychological altruism: a reassessment Armin W. Schulz Biol Philos (2011) 26:251–260

- Ibid. p.259

Bibliography

Sober E. and Wilson D.S. 1998. Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Stich S (2007) Evolution, altruism and cognitive architecture: a critique of Sober and Wilson’s Argument for psychological altruism. Biol Philos 22:267–281

Sober, E. (1993a). Evolutionary Altruism, Psychological Egoism, and Morality: Disentangling the Phenotypes. In M. Nitecki (ed.), Evolutionary Ethics, SUNY Press, pp. 199-216

Sober & Wilson’s evolutionary arguments for psychological altruism: a reassessment Armin W. Schulz Biol Philos (2011) 26:251–260